If your loved one has recently had a stroke, you have likely heard about the various physical impairments that are common after a stroke. From decreased mobility of the arms and legs to tongue weakness, these impairments can be difficult for individuals and their families to deal with.

One of the most troubling post-stroke impairments is difficulty swallowing due to dysphagia, or the inability to safely transfer food from the mouth to the stomach.

Thankfully, there are numerous ways to help rehabilitate someone’s ability to swallow without putting them at risk of choking or aspiration.

Keep reading if you’d like some tips on how you can help regain swallowing following a stroke.!

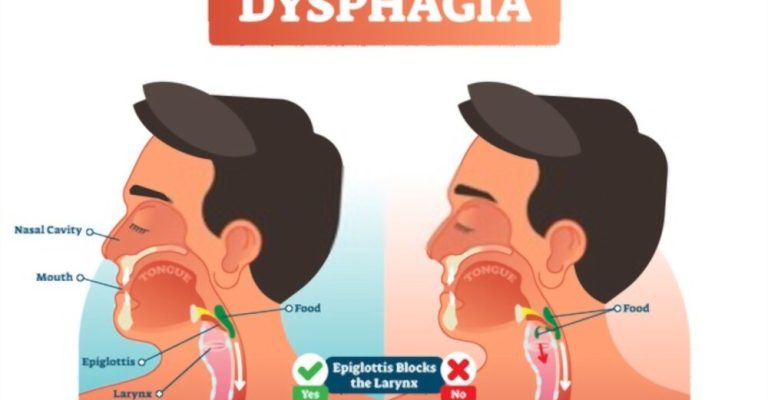

Dysphagia is the “impaired ability to move food or liquid from the mouth to the stomach for proper digestion.” It is a condition that affects many people who have experienced a stroke.

Dysphagia can cause an individual to experience difficulty chewing and swallowing, leading to dehydration, malnutrition, and the risk of choking or aspiration. Therefore, individuals with dysphagia must receive the help they need to regain their ability to swallow safely.

Knowing the signs to look for may help you identify and treat swallowing disorders before they become life-threatening. Some warning signs of swallowing difficulties are:

Many different factors can contribute to dysphagia following a stroke. Some of the most common causes include:

Oropharyngeal dysphagia, induced by the stroke’s effect on the brain, affects the majority of stroke patients.

Impairment to the motor cortex or brain stem, the area of the brain responsible for controlling the neck muscles, prevents the brain from sending nerve impulses to the throat muscles. Therefore, the survivor’s capacity to regulate swallowing muscles may be impaired, resulting in dysphagia.

Dysphagia is a swallowing disorder that may vary from little difficulties to complete incapacity in people who have had a stroke. Those with trouble swallowing may need to rely on soft meals or, in extreme situations, a feeding tube to get the nutrition they need to survive.

Thankfully, most people who survive a stroke have a significant improvement in their dysphagia within the initial 2 weeks. Rehabilitation increases the likelihood of long-term healing and a return to normal swallowing for those who do not see a rapid recovery.

Dysphagia is a condition that may lead to major problems if treatment is delayed. So let’s talk about these problems before we go into the treatment techniques.

Disturbance in swallowing, or dysphagia, is a significant medical issue. These can include:

People with dysphagia are susceptible to aspiration pneumonia, which can be fatal in an already weakened body.

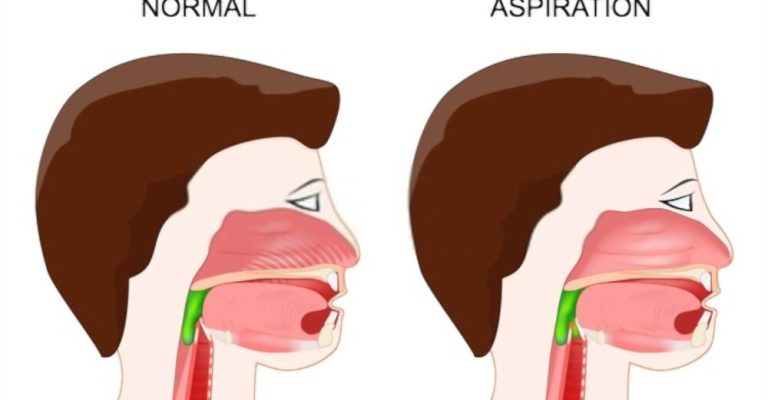

When food or drink is accidentally inhaled, it is a dangerous complication for patients with dysphagia. If your throat and esophagus muscles aren’t working correctly, you can aspirate food or drink instead of swallowing it. This might introduce germs into your lungs.

Individuals with dysphagia are unable to consume sufficient food and liquids to maintain healthy nutrition, which can lead to other health issues. They can become malnourished and dehydrated, exacerbating any existing health issues.

Moreover, some survivors need to employ thickening substances to thicken their diets, which may be unappealing and lead to meal skipping.

Studies suggest that as many as 20% of stroke survivors are underweight, highlighting the need for vigilant nutrition monitoring.

Dysphagia can also cause choking, which can be a life-threatening emergency. When you choke, the airway becomes blocked, and you can’t breathe.

Choking can happen when food or liquids go down the “wrong pipe” and get lodged in your windpipe or throat. When in the hospital, patients with dysphagia need to eat and be regularly monitored by a speech-language pathologist, also known as a speech therapist.

They will check on patients to ensure sure they are well enough to eat on their own before releasing them from the hospital. Having a trusted adult, such as a parent or guardian, nearby is essential for safety.

According to research, most people with dysphagia get well within two weeks, and it affects around half of those who survive a stroke. Recovery, meanwhile, will be unique for each person because of the various factors contributing to stroke.

Dysphagia may sometimes resolve on its own, a process known as spontaneous recovery. In cases where the stroke was relatively minor, full recovery may occur without treatment.

For the most part, the severity of a stroke correlates with how long the symptoms of dysphagia last after the stroke has occurred. If malnutrition is a concern due to serious dysphagia, a catheter may be necessary at first but may be withdrawn when swallowing capacity increases.

While the amount of time it takes to recover from a stroke may vary significantly from one person to the next, it is possible to speed up the process and improve the odds of a full recovery by sticking to a structured rehabilitation program.

Many people who have had a stroke may regain the ability to swallow with the help of therapy. In addition, the ability to eat and maintain a high quality of life may be enhanced by motor-specific rehab techniques that make swallowing simpler and more effective.

Take these measures to enhance your likelihood of swallowing again after a stroke:

When it comes to difficulties with swallowing, such as dysphagia, it’s best to see a speech-language pathologist who has extensive training in the area. Although swallowing does not need vocalization, it is classified as speech since it utilizes the mouth muscles.

Therefore, an SLP is qualified to evaluate your specific situation and devise a rehab plan to help you recover.

Your speech therapist will probably give you some swallowing techniques. Although these techniques may not need actual swallowing, they will assist in strengthening the mouth’s muscles and increase one’s command of oral motor skills.

Neuroplasticity, the brain’s natural ability to form links and repair after injury or illness, is the primary mechanism through which speech and swallowing practices work to restore function.

The repeated motion of swallowing activities promotes neuroplasticity and the growth of new brain networks, which in turn enhances motor skills. As a result, you may improve your chances of recovering swallowing function with time and effort.

Get some swallowing practices from your speech therapist to work on in your own time. The following procedure will be helpful in this regard as well.

Electrical stimulation is a common technique used in stroke rehabilitation, although most people only associate it with intending to restore full mobility in the legs or arms. Nonetheless, electrical stimulation may aid in rehabilitating all motor abilities, including those involved in swallowing and eating.

Soft electrical impulses stimulate the muscles in and around the neck. In order to promote neuroplasticity, this provides additional stimulus to the brain.

In addition, more and more research suggests that combining electrical stimulation with rehabilitation activities might improve outcomes.

Regaining swallowing function after a stroke may be accomplished via a variety of treatments, but it takes time for patients to see gains from swallowing practices and electrical stimulation.

Meanwhile, it’s crucial to prevent harm by avoiding situations where you can choke or have silent aspirations, which occur when food or liquid is inhaled into the lungs without causing any apparent symptoms.

Following these guidelines will help you stay safe while dealing with dysphagia:

Stroke survivors who are dealing with dysphagia may feel discouraged initially. Unfortunately, Dysphagia is a common problem among stroke survivors, but it may be overcome with the correct information, attitude, support system, and professional help.

References:

https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/dysphagia

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4066736/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5809242/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2563739/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326735/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4630679/