A singular manifestation of aberrant body posture manifests itself in somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of post-stroke patients. The term “Pusher Syndrome” was first defined by Patricia Davis in 1985.

Davis was the first person to describe this behavior. When not supported, these patients show a loss in lateral posture by falling onto their paretic side. This is because of their paretic condition. Pusher syndrome is frequently characterized by severe inattention as well as abnormalities in hemisensory function.

Pusher behavior may be the result of a conflict between an impaired somesthetic perception of vertical and an intact visual system, or it may be the result of a high-order disruption of somatosensory information processing from the paretic hemi-body.

Both of these hypotheses have been proposed as possible explanations for the phenomenon. Patients diagnosed with Pusher Syndrome may further suffer from primary visual or visual perception difficulties, reduced proprioception, and motor impairments, all of which make it more difficult for them to regain proper posture and balance.

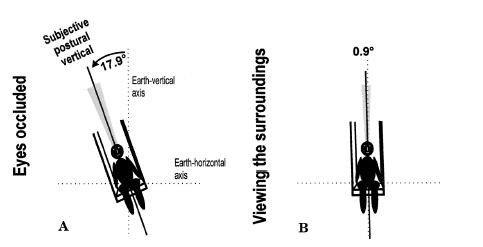

Patients with Pusher Syndrome exhibit a misunderstanding of their upright body posture, as demonstrated by Karnath et al. Patients with Pusher Syndrome report having an “upright” posture even though their bodies are actually tilted 18 degrees to the ipsilesional side.

Patients who were included in this study frequently showed damage to either their left or right posterolateral thalamus when they underwent MRI scanning after suffering a stroke.

However, the information concerning the site of the infarct is contradictory, with other studies also indicating damage to the parietal region. Several earlier research revealed that individuals with injury to the right side of the brain were more likely to exhibit pusher behavior than patients with damage to the left side of the brain.

It was also hypothesized by Abe et al. that individuals who had suffered an injury to their right hemisphere were more likely to suffer from Pusher Syndrome.

According to the findings of a review conducted by Paci et al., the variety of symptoms associated with Pusher Syndrome may be the result of a multidimensional network that is in charge of maintaining upright postural regulation.

The following symptoms were found to be present in individuals diagnosed with Pusher Syndrome by Kim and Seok-Hyun:

As may be seen in the following table, Karnath and Broetz have identified three diagnostic criteria for Pusher Syndrome.

It is necessary to check for contralateral tilting in the patient’s initial posture, which is displayed soon after a positional change (preferably from supine to sit or sit to stand). This can be observed even in the absence of the patient falling over to the side that is affected by brain damage. It is generally agreed upon that patients must exhibit this postural abnormality on a consistent basis in order for them to be identified as having Pusher Syndrome.

Patients have an aberrant alignment of the side of their body that is ipsilateral to the brain injury. In most cases, the elbow will be held in a fully extended position, and the hand will look for a surface on which it may make contact in order to propel the person toward a position that is seen as being upright. Abduction of the lower limb is possible while maintaining extension of the knee and hip joints (as with the upper limb).

Patients will often put up a fight against their therapists’ attempts to modify their body posture through the use of physical therapies. The patient’s extended upper and lower limbs will be utilized in order to shift their weight onto the side of their body that is affected by paralysis.

Because of this, the Standardized Scale for Contraversive Pushing, also known as the SCP, was developed based on these three deficiencies. The SCP is a helpful tool for physicians to categorize Pusher Syndrome, and it can be applied quickly and easily in both an acute environment and a rehabilitation context.

It was suggested by Bergmann et al. that the Burke Lateropulsion Scale is more responsive in identifying Pusher behavior and is more sensitive to slight changes in presentation than the Scale for Contraversive Pushing. In addition, it was indicated that the Burke Lateropulsion Scale is very helpful in detecting mild or moderate pusher behavior in standing and walking. This was suggested as a result of the fact that the Burke Lateropulsion Scale was developed.

There is a lack of consensus in the research on whether or not Pusher Syndrome will continue to manifest itself over the course of a longer period of time and what effect it will have on the functional result. It has been reported by some authors that the occurrence of Pusher Syndrome is uncommon six months after a stroke, and it has been proven to have no negative impact on the patients’ eventual functional outcome, despite the fact that it has been observed to slow rehabilitation by up to 3 weeks.

However, a case study that was conducted by Santos-Pontelli and colleagues indicated the persistent existence of Pusher Syndrome in three patients up to two years after they had suffered a stroke.

This had a significant negative influence on the patient’s capacity to do functional tasks.

Approximately 59 percent of the time, patients who had two deficiencies were successful in reaching the goal. However, only 37 percent of patients were able to reach a score of 0 or 1 on the Burke Lateropulsion Scale prior to being discharged from the hospital. This was the case for patients who had a motor, proprioceptive, and visual–spatial deficits as well as hemianopia.